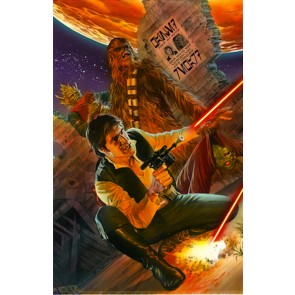

Alex Ross

Born in Portland, Oregon, and raised in Lubbock, Texas, Alex made his artistic debut at three when, according to his mother, he grabbed a piece of paper and drew the contents of a television commercial he’d seen moments before. Ross came from an artistic family: his mother was a commercial artist and his grandfather, he recalls, "built working wooden toys and loved drawing." When Ross discovered Spider-Man on an episode ofThe Electric Company, his life was changed forever. "I just fell in love with the notion that there were colorful characters like this, performing good, sometimes fantastic deeds," Ross says. "I guess I knew this was what I wanted to do. I wanted to bring these characters to life."

Born in Portland, Oregon, and raised in Lubbock, Texas, Alex made his artistic debut at three when, according to his mother, he grabbed a piece of paper and drew the contents of a television commercial he’d seen moments before. Ross came from an artistic family: his mother was a commercial artist and his grandfather, he recalls, "built working wooden toys and loved drawing." When Ross discovered Spider-Man on an episode ofThe Electric Company, his life was changed forever. "I just fell in love with the notion that there were colorful characters like this, performing good, sometimes fantastic deeds," Ross says. "I guess I knew this was what I wanted to do. I wanted to bring these characters to life."

Some cynics might confuse this attitude with escapism. For Ross, it’s just the opposite. "It’s a fun environment to be in," he admits. "Superheroes are a mixture of every form of fiction – myth , science-fiction, mystery and magic – all in one giant pot. The best characters embody virtues we may try to find in ourselves."

Ross is quick to credit his father Clark, a minister, with laying the moral framework that allowed him to appreciate the routinely good deeds performed by the likes of Superman and Spider-Man. "My dad has given aid -- physical aid, not just financial -- to a number of charities and causes. He’s helped at homeless shelters. He used to run a children’s shelter in Lubbock. There was a positive effect to being around him, and his actions tied into what the superhero comics were teaching me. Superheroes aren’t heroes because they’re strong; they’re heroes because they perform acts that look beyond themselves."

As he edged towards adulthood, Ross began reading comics and taking his draftsmanship seriously, admiring the work of comic book illustrators George Perez and Berni Wrightson in particular. "They were at opposite ends of the spectrum," Ross recalls. Wrightson, probably best known as the co-creator of Swamp Thing, "used a lot of delicate lines to delineate shadow and tone. There weren’t a lot of comic book artists employing shadows back then. Perez, on the other hand, had a very attractive, open style with open contour lines and very little shadow. When I was 12, I would imitate Perez’s style when I drew superheroes and Wrightson’s style when I was doing ‘serious’ work. I realized there was no one way to go."

This philosophy became especially true when Ross discovered such illustrators as Andrew Loomis and the great Norman Rockwell. "I idealized people like Rockwell, who drew in that photorealistic style," Ross says. "When I was 16 or so, I said to myself, ‘I want to see that in a comic book!’"

Even as a young man, however, Ross knew "there was no satisfaction in basing my style upon the work of someone else." So, while his friends were exploring the uncharted territories of adolescence, Ross devoted his time to becoming a draftsman, with the long-term goal of making people believe a man could fly.

"High school can be a chaotic time," he says. "Through my art and through what these characters represented, I found a sense of order that I wanted to apply to my life. It’s not that I wasn’t interested in dating or socializing. It’s just that part of me didn’t want to let go of the colorful characters I’d loved for so long."

At the age of 17, Ross went to Chicago and began studying painting at the American Academy of Art, the school where his mother had studied. "My time at the Academy was really valuable," he recalls. "I learned where I was as an artist and what kind of discipline I’d already learned. Here I was, drawing from a model for the first time and realizing I could represent the model. Not everyone in the class could do that. It was important to make that discovery."

Studying at the Academy also allowed Ross to examine fine art in greater depth. "Salvador Dali wound up being a big influence, actually," he says. "He had a vivid imagination and a hyper-realistic quality that wasn’t so far removed from comic books. I began to study the classic American illustrators like Rockwell, J. C. Leyendecker… I’ve been called ‘The Norman Rockwell of comics’ more than a hundred times. I’m not going to suggest I’m on the same level as Rockwell, but attempting that sort of realism in my work has always been part of my approach."

It was at the Academy that Ross hit on the idea of painting his own comic books. "There wasn’t any moment where I saw the light and said, ‘Painted comics! That’s the way!’" he recalls. "It was a by-product of my studies. There wasn’t any program that taught me to ink a comic book. There were programs that taught me to paint. I just naturally thought, ‘Well, of course I’m going to apply that to comics.’ There were also enough painted comics out there -- not a lot, but a few -- that made me think that talent could be applied."

There was also, Ross admits, a sense of wish fulfillment involved. "Hopefully by painting the work, you gain a sense of life and believability that will draw the reader in a little more. You can use color and light and shadow and live models to give the work a certain realism. It might be easier to relate to a character if you look at it and say, ‘Here’s an actor portraying someone. Here’s something that looks real.’ I thought it would draw people in and maybe add to their enjoyment of the work. There’s also a part of me that likes to speculate: ‘What if they made a movie about this character?’ I realize some of my favorite characters will never get the movie treatment, so it’s up to me to present them in a lifelike fashion, to make the movie that would otherwise never get made."

After three years at the American Academy, Ross graduated and took a job at an advertising agency. Meanwhile, Marvel Comics editor Kurt Busiek had seen Alex’s work and suggested the two men collaborate on a story. Those plans came to fruition in 1993 with Marvels, a graphic novel that took a realistic look at Marvel superheroes by presenting them from the point of view of an ordinary man. The book landed Ross his first serious media exposure, both within the industry and outside it. Fans appreciated that Ross had an obvious affection for the characters he painted, demonstrated by his attention to detail and the fact that he took the time to make these characters look so believable.

Ross followed up Marvels with Kingdom Come, a futuristic story for DC Comics about a minister who must intercede in a superhero Civil War. It was a visual feast, filled with surprise cameos, in-jokes and a main character based on Ross’ father, allowing Ross to publicly acknowledge his family’s influence.

Having established himself creatively and financially with superhero projects, Ross turned to the real world with Uncle Sam, a 96-page story that took a hard look at the dark side of American history. Like Marvels andKingdom Come, the individual issues of Uncle Sam were collected into a single volume – first in hardcover, then in paperback – and remain in print today.

Ross’ recent works have celebrated the 60th anniversaries of Superman, Batman, Captain Marvel and Wonder Woman with fully painted, tabloid-sized books, depicting each of these characters using their powers to inspire humanity as well as help them.

"I do the gigs I do because I care about the material," he says. "In some cases, it’s because I like the character. In some cases, I have a vision in my head of something I must do. It all involves artistic expression. If I can’t get into the work on some artistic level, I can’t do it."

In recent years, Ross has applied his artistic skills to outside projects with comic book roots, including a limited-edition promotional poster for the 2002 Academy Awards. A number of items created especially for the Warner Bros. Studio Stores – including lithographs, collector’s plates and even a canvas painting of Superman – made him the best-selling artist in the chain’s history.

In the fall of 2001, Ross painted a series of four interlocking covers for TV Guide (featuring characters from the WB series Smallville) and designed and sculpted a series of busts based on characters he created for the Marvel series Earth X. "Designing the statues," Ross explains, "was a case where I said, ‘Hey, I know I can do this, and before somebody else does it – maybe differently from the way I would like it done – I can sculpt some of the characters for which I’m well-known and make sure they look the way I want them to look.’ My comics work notwithstanding, I prefer not having to rely on the labors or plans of others. For the fans’ sake as well as for my own, I want to take full responsibility for the projects that bear my name."

Forty years ago, Spider-Man learned that with great power comes great responsibility. Looking at Alex Ross, it’s obvious the lesson took. Ross’ career offers another important message: follow your dream. Actually, it’s not far from the sort of message you might find in one of his stories.

Loading...

Loading...